… and so much confusion about what it all means. Here’s what companies should – and shouldn’t – be looking at to help their business.

WHEN IT COMES TO online retailing, a lot of knowledge doesn’t necessarily take you a long way.

We retailers, it would seem, have a big advantage over their offline counterparts: They can track every virtual step a shopper takes – what Internet path she took to the store, what products she viewed and at exactly what point she made the decision to leave without buying anything.

By using what are known as “data mining” programs, online retailers can take all this information and create powerful profiles of shoppers and their buying habits. Retailers can tell not only how many customers bought the new Tom Clancy novel, for instance but also how many of those bought “Sylvia Browne’s Book of Dreams” as well. And the billing and shipping information that nearly every online sale requires enables retailers not only to track individuals’ purchases closely but also to analyze broad buying patterns – by gender, at least, and even by Internet-service provider, if an e-mail address is given. That’s a wealth of data that can be used to target marketing efforts.

What’s wrong with this picture? Put it under the category of Too Much of a Good Thing: With all this data at their fingertips, many retailers end up chasing information down what Forrester Research Inc. analysts Kate Delhagen calls “data ratholes.”

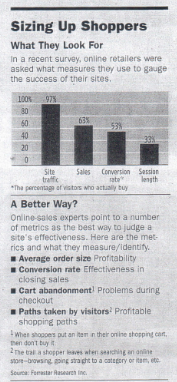

“There are a lot of data flowing through their companies, but a lot of it is minutiae,” says Ms. Delhagen, retail research director at Forrester, in Cambridge, Mass. “They go crazy trying to do that level of analysis.” Indeed, over a third of online retailers surveyed by Forrester in March said they have trouble understanding shoppers’ behaviour.

So how can retailers harness this flood of information in a way that actually helps their business – that is, to boost sales? How do they ignore the noise and hear the chords worth listening to? The answer to some extent depends on the specific business and goals. But the basic rule, data experts say, is this: Don’t focus on how many shoppers are visiting a site on what they’re doing when they get there.

In many ways, that runs counter to what online companies have long pointed to as evidence of their success. Visitors, eyeballs, traffic – this is the stuff online companies often cite as indications of their popularity.

Instead, data-mining experts say, the most useful data answer specific questions about shoppers’ behaviour on a site. Do they abandon their shopping carts when they get to the shipping charges? Do they quit the site if they have to browse through too many screens to find what they’re looking for? Will they spend more if you show, say, a shirt after they buy a pair of pants, but not if you show a jacket?

“A lot of it is about going back to the basics,” says Usama Fayyad, president and chief executive of DigiMine Inc., a Bellevue, Wash., data-mining company. “Am I serving the customer? Are they finding what they’re looking for? Are we making them happy?”

Babystyle, which sells clothing and other goods for pregnant women and for children, addressed this problem with the help of analysis by Coremetrics Inc., a company based in Burlingame, Calif., that compiles and analyzes information about online shopping activity. Babystyle found that only 61% of those who began the checkout process on its site were getting past, the page where they entered their billing information, and only about 47% were getting through the entire four-step process.

That information prompted Babystyle’s parent, Lo Angeles-based estyle Inc., to rebuild the checkout process. Shoppers now can store multiple shipping and billing addresses and credit-card numbers, allowing faster checkout for repeat customers. At the same time, the site added a step that made checking out less confusing for customers using coupons or gift certificates.

After the changes, the proportion of shopping carts abandoned on the Babystyle site dropped to 38% from 53%.

“Optimizing the checkout process is perhaps the most meaningful, low-hanging fruit.” In the quest to convert shoppers to buyers, says Lariayn Payne, estyle’s vice president of marketing. “The concept is simple, and the upside is significant.”

THE LESSONS OF SUCCESS

What about the shoppers who aren’t abandoning their carts? What can online retailers learn from their paying customers? On concern for any retail operation is how the display of products and the layout of the store affect sales. And this is an area where online retailers can use the Web’s feedback to particular advantage.

Victoria’s Secret, like other cataloguers, has a lot of experience with this in the print world. The seller of women’s lingerie, a unit of Limited Brands Inc., Columbus, Ohio, mails out several catalogs a year, featuring largely the same merchandise but with different covers and product photos. Then it gauges which generates the most sales.

Offline, this can take several months, but online the response to different presentations can be measured almost instantly, and in more detail. In a recent instance, a lace-up Victoria’s Secret gown was selling well in the site’s “top 10” area, but was lagging, in the section of the site for gowns, where it was displayed on the second of several screens. By making it more prominent in the gown section, marketers were able not only to increase sales from the gown section, but to increase total sales of the gown as well.

Ken Weil, the company’s vice president of new media, says such adjustments can increase sales of an item by as much as 20%. “We’re able to influence sales, and therefore profits, by how we adapt” to th data, he says.

Petco.com, the online store of pet-supply retailer Petco Animal Supplies Inc., used Web feedback in a similar way, to determine the effectiveness of a new traffic pattern. Petco.com’s marketers wanted to add a “button” that would take shoppers from the home page to a page featuring monthly specials. But the site already had a tab on its navigation bar and a link at the bottom of the home page to the specials page. He marketers worried that the extra link would clutter up the home page and only split existing sales from the specials page with the other two links.

Instead, they discovered that the extra link boosted total traffic from the specials page by about 10%. What’s more, they determined that while the three links split the number of visitors to the specials page about equally, the new button drove significantly more sales.

“People having different ways that they browse,” says Heather Blank, director of e-commerce marketing at San Deigo-based Petco. “We basically just realized that it didn’t hurt us to link to one area from more than one place.”

MISSING THE MARK

That sort of insight doesn’t come from some of the more popular Internet data. Consider site visits: Te number of visitors to the site may show you’re attracting a lot of shoppers, but it won’t tell you why some are buying and some aren’t. “Traffic for traffic’s sake is not a metric that retailers ought to be focused on,” says Carrie Johnson, a Forrester analyst.

Another common red herring is data on buying patterns across product lines. “Say you’re a department store and you find that people who are buying Levi’s are also buying china,” says Scott Silverman, executive director of Shop.org, the online arm of the National Retail Federation. “Should I start making china a suggestion for people who are buying jeans? Just because they are patterns doesn’t mean there is a relationship.” A recent Forrester study found that was recommended to them, compared with about half who bought an item they were already searching for.

Still, some data evangelists dismiss the idea that any information about customers and their behaviour can be useless. It’s all about zeroing in on the information that drives sales at a particular retailer’s site. “The only bad data is someone else’s data,” says Scott Kauffman, president and chief data,” says Scott Kauffman, president and chief executive of Coremetrics, “because it isn’t relevant to your business.”

By: Michael Totty

Source: The Wall Street Journal