Clusters of internet firms are popping up all over the region

WHEN Fida Taher decided in early 2011 to launch a website showing recipe videos, her family laughed. Not only were her cooking skills mediocre; she had no experience in business. And she was leaving a good job at a video-production company. “But I had stopped learning there and felt too young to settle,” she explains.

Today Ms Taher’s firm, Zaytouneh (“olive” in Arabic), boasts 600 visual recipes, from frying salmon to baking doughnuts. The short clips, which show only the ingredients and the hands of the cook, are a hit on YouTube and other websites. In May Zaytouneh, which now has a dozen employees, attracted financing from a satellite broadcaster, which will also air its videos. Several of the region’s mobile-telecoms operators will carry them, too.

The story sounds like a common one from Silicon Valley or Silicon Roundabout, London’s start-up district. But Ms Taher tells it in a café in Amman. She is just one of several hundred entrepreneurs, many of them women (see article), who have started online firms in Jordan’s capital in recent years, making it one of the Middle East’s leading start-up hubs. Even more surprising, such clusters (“ecosystems” in the lingo) have been popping up all over a region that is better known for armed conflict and political strife. Whether in Beirut, Cairo, Dubai, Riyadh or even Gaza City, small technology firms are multiplying, creating a sort of “start-up spring”.

As with its political predecessor, nothing seems to stop the region’s entrepreneurs—not bureaucracy, not the fear of failure and not religion. “After all, Prophet Muhammad was a trader,” says Fadi Ghandour, who in 1982 co-founded Aramex, a logistics firm based in Amman, and now spends much of his time helping build the region’s start-up ecosystems.

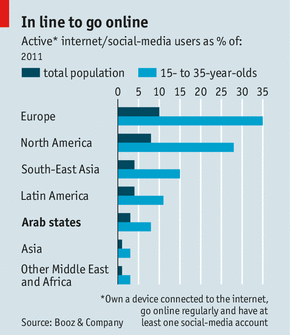

Most of these young firms will not make it, but for those that survive a bright future beckons. Although the Arab world is behind other regions in internet use (see chart), it is catching up fast, along with smartphone penetration and e-commerce. What is more, cultural and linguistic barriers provide some protection against foreign internet giants.

That said, the region’s tech clusters are still tiny compared with Silicon Valley or even Israel, the “start-up nation” next door. But “the rise of a new generation of business entrepreneurs cannot be ignored,” writes Christopher Schroeder, an American investor, in “Startup Rising”, a book about the region’s wave of tech entrepreneurialism, published next month.

At worst the trend could be just a local internet bubble that will leave many disappointed. At best it may set an example for how countries in the region might tackle one of its biggest problems: youth unemployment. By some estimates more than a quarter of the population aged between 15 and 24 have no job.

Although start-ups are popping up across the Middle East, Jordan’s ecosystem is the most evolved. The country lacks oil riches, but boasts a good education system and many graduates. The first local information-technology firms were founded in the 1970s. Today firms range from the likes of Palma Consulting, which helps companies implement software, to Aspire, which maintains computer systems.

Being more fun-loving than some of its neighbours, the country is also home to some of the region’s leading media and gaming companies. Rubicon, for instance, produces a wide range of content, from films to online training courses. Maysalward develops popular mobile games. Most of the region’s online-gaming revenues flow through gate2play, a payment service which also serves web merchants.

Some of the credit for Jordan’s lively internet start-up scene goes to King Abdullah, the country’s ruler, who does not hide his penchant for digital technology (in particular video games). After ascending the throne in 1999 he set out to make life easier for start-ups, explains Fawaz Zu’bi, who became the country’s first communications and IT minister in 2000. Today it takes days rather than months to register a new firm. And internet connectivity is among the best in the region.

But the breakthrough came in 2009 when Maktoob, a Jordanian internet portal, was sold to Yahoo for $175m. “That showed people what is possible,” says Samih Toukan, one of Maktoob’s founders. He now heads Jabbar, a group of internet firms, which recently spun out two other businesses, Souq, an e-commerce site, and cashU, another mobile-payment service.

The deal inspired not only other entrepreneurs, but organisations that bind them together. Now, every first Tuesday of the month, an event called TechTuesdays attracts hundreds to discuss both technology and business issues such as how to bounce back from failure. A start-up called Wamda provides a steady flow of information online for entrepreneurs, organises events for them in the real world and invests in some.

Maktoob’s sale also led to the creation in 2011 of an “accelerator”, a sort of school for start-ups, whose backers include the king. It has since become the heart of Amman’s high-tech ecosystem. During three months of intensive work and not much sleep, small teams of founders develop products, find customers and learn the basics of business, mentored by experienced entrepreneurs. Finally, Oasis500, as the accelerator programme is called, organises a “demo day”, during which the teams pitch their start-ups to investors.

Pillars of wisdom

The pillars in Oasis500’s open-plan offices are covered with famous quotes in Arabic (“I will surmount difficulties or die trying”, says one). But otherwise the space evokes the headquarters of a tech firm in Silicon Valley: Oasis500’s two floors, connected by a slide, are packed with folk in their 20s hunched over laptops. In one corner a team is working on an online store for musical instruments, which can be hard to buy outside the region’s big cities. Another table serves as headquarters for a firm making management software for schools. It has just won a contract in Saudi Arabia. A third firm, co-founded by a refugee from Syria, allows users to order healthy meals from restaurants in Amman.

When they are not working on their start-ups, the teams take classes in the basement. This is also where Oasis500 applicants do “bootcamp”, a gruelling one-week course in business. “It’s better than any due diligence a venture capitalist can do. You can tell whether they are willing to give up family commitments for their start-up,” says Usama Fayyad, once chief data officer at Yahoo, now Oasis500’s boss.

By several measures the accelerator is a success. About 1,000 candidates have taken part in the bootcamp (a quarter of them women). More than 60 start-ups have so far been picked for the programme, which comes with an investment of $30,000 ($14,000 in cash and $16,000 in services, such as workspace and legal advice). Nearly half of the alumni have found follow-on financing. Most are still in business. And Oasis500’s managers say fresh applications are coming in at a rate of 350 a month.

New firms now have a good chance of getting started, but in Jordan as elsewhere in the Middle East, “starting something up is cheap, but scaling it into a real business is hard,” says Habib Haddad, the chief executive of Wamda. There is plenty of money sloshing about, but investors prefer safe, tangible bets such as property and factories over putting their cash into high-risk start-ups. “Venture capital is an animal people here can’t quite understand,” explains an American executive who is raising a fund in Dubai. “Investors often ask: ‘What do you mean, you can lose all the money?’” In Jordan venture capital is in short supply and “angel” investors, who bet their own fortunes, are inexperienced—they soon flee if financial success does not come as planned.

Already, several start-ups in Amman have shut down for lack of follow-on financing. Valuations have dropped since the post-Maktoob euphoria. Oasis500 has doubled the stake it takes in start-ups in its programme to 20%, meaning that their initial valuations are cut in half.

Once start-ups have found the few hundred thousand dollars required to expand, they must tackle the next hurdle: the region’s fragmentation. Each country has its own culture and laws. E-commerce firms also have to deal with high tariffs, slow border bureaucracies and bad infrastructure. Goods often cannot be transported by lorry or train, but have to be flown in.

Still, being born in a small country, start-ups in Jordan need to think internationally from day one. Many move sales and marketing to one of the free-zones in Dubai (which are spared some taxes and regulations). From there it is much easier to hire foreign talent and enter Saudi Arabia, the region’s juiciest market. With a population of 28m, the Saudi kingdom not only boasts a lot of consumers, but ones with money to spare, good internet connectivity and not much else to do. On average Saudi netizens watch three times as many online videos a day as American ones.

Pilgrimage to Saudi

At a recent Wamda event in Amman, participants traded tips on how best to make this entrepreneurial pilgrimage: which free-zone in Dubai is the cheapest (some let firms rent just a desk rather than an entire office); what it takes to get a visa for Saudi Arabia (it is essentially a lottery); and how to set up a company there (for each foreign employee you may on paper have to hire two Saudis, who then never show up to work). “Saudi is not user-friendly, but we can’t do without it,” says Zafer Younis, boss of The Online Project, which develops social-media strategies for big companies.

Having a presence in Saudi Arabia certainly helps to get more financing. It may also be a requirement for overcoming what may be the thorniest problem, at least for entrepreneurs who want to make it big: an “exit”, meaning either being bought by a bigger firm or going public. “Since Maktoob we had many good start-ups and a new level of investments, but no important exits,” says Muhannad Ebwini, the boss of gate2play.

Is the Middle East’s start-up spring bound to disappoint, like its political predecessor? “Jordan’s ecosystem is very promising, but also very young. There will be growing pains,” warns Fouad Jeryes, who co-founded TechTuesdays and Hyper, a service that picks up the cash before an online order is delivered. (This is a useful offering in a region where many do not have credit cards and goods are paid for on delivery, which often goes wrong.)

Much depends on what steps governments take to encourage entrepreneurialism. Jordan’s experience shows the way: it has cut red tape, improved education, created competition in telecoms and seeded accelerators. But it also helps not to pass restrictive media laws as Jordan, worryingly, has recently done: it now requires news websites to register with the government and has blocked more than 300 which have not done so.

Making life easier for tech start-ups will not by itself be sufficient to get young people off the street. Most do not have the skills to work in such firms, nor will these create enough jobs. But the emerging tech ecosystems provide a model of how other industries, too, could become more vibrant—if governments would only set them free. “We have no choice”, argues Randa Ayoubi, the boss of Rubicon, “but to let people create their own jobs.”